views

Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) belongs to the family Bacillaceae classified on the basis of their phenotypic and molecular characteristics. The cells of B. anthracis are Gram-positive rods that are aerobic, facultative anaerobes. They are capsulated and can form spores, living in soils worldwide at mesophilic temperatures. The cells of the size ranging from 1.0-1.2 µm in width and 3.0-5.0 µm in length occur either singly or in pairs. In the clinical samples, however, cells might appear in short chains.

Fig. 1 A Gram-stained culture sample, depicts chains of Gram-positive, rod-shaped, Bacillus anthracis bacteria (CDC/ Dr. James Feeley, 1980)

Fig. 1 A Gram-stained culture sample, depicts chains of Gram-positive, rod-shaped, Bacillus anthracis bacteria (CDC/ Dr. James Feeley, 1980)

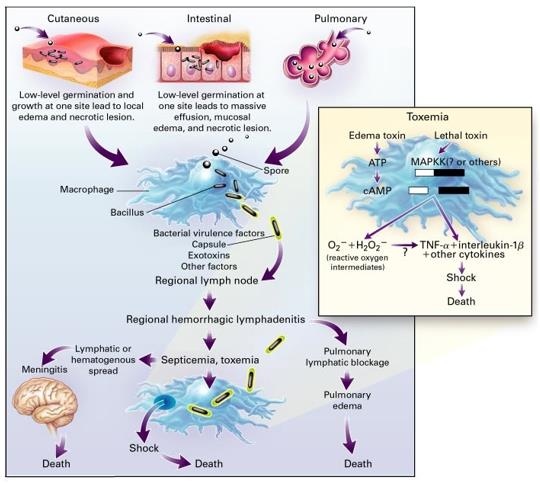

Anthrax infections are initiated by endospores of B. Anthracis that causes bacteraemia and toxemia in its systemic form through an array of virulence factors. The most common form of anthrax infection is cutaneous anthrax which accounts for about more than 90% of all human cases. The other two forms of anthrax are gastrointestinal anthrax and pulmonary or inhalation anthrax; the latter being most fatal among all the modes of infection. B. anthrax is also associated with meningitis. The cycle of infection of B. anthracis begins with the ingestion of spores, which in the case of animals occurs from the soil while in humans, it is transmitted from the animals after frequent exposure. The extraordinary virulence of the bacteria is due to the virulence factors that enable the survival of the bacteria as well as its ability to cause destruction of the host cell during its infectious life cycle.

Fig. 2 Pathogenesis of Bacillus anthracis (Dixon et al., 1999)

Fig. 2 Pathogenesis of Bacillus anthracis (Dixon et al., 1999)

The clinical diagnosis of B. anthracis infections is confirmed by the visualization and culture of B. anthracis from the clinical samples. The samples used for the identification of B. anthracis include swabs for collecting vesicular fluid in the case of cutaneous anthrax. There are several common methods for B. anthracis laboratory diagnosis:

- Cultural and Biochemical Identification: The conventional method of diagnosis of anthrax has some challenges due to the phenotypic and genetic similarity with other Bacillus species.

- Antigen-based Methods: Common immunoassays used for B. anthracis identification are flow cytometry assays and luminescent adenylate cyclase assays.

- Molecular Methods: Molecular methods like PCR involving the DNA amplification method facilitate the detection of B. anthracis without the culture of the bacteria, which makes them safer than the conventional methods. However, there are some challenges with using these genes as the plasmids can be lost or transferred to other Bacillus species.

The bacteria is sensitive to many antibiotics. It is resistant to cephalosporins, sulfonamides, and trimethoprim. Currently, treatment with ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and doxycycline is recommended in the cases of mild cases of cutaneous anthrax. BioThrax® Anthrax Vaccine Absorbed (AVA) is produced by Emergent BioSolutions, Inc., and is the only anthrax vaccine licensed by the FDA. AVA is a cell-free filtrate made from cultures of a strain of anthrax not capable of causing disease. A 5-dose series is required for immunization, with annual boosters. Anthrax Immune Globulin (AIG) antitoxin is a therapy derived from the plasma of individuals previously immunized with the anthrax vaccine. This investigational product consists of antibody directed against the anthrax protective antigen. Raxibacumab (ABthrax), a human monoclonal protective antigen-targeted antibody developed by Human Genome Sciences (HGS), targets anthrax toxins after they have been released by anthrax bacteria, when antibiotics might not be effective.

References

- Bacillus anthracis (Anthrax). (2014). UPMC Center for Health Security.

- Anupama S, (2022). Bacillus anthracis- An Overview. Microbe Notes.

- Dixon TC, Meselson M, Guillemin J, et al., (1999). Anthrax. New England Journal of Medicine, 341(11), 815-826.

- Turnbull P, (2008). Anthrax in Humans and Animals. Geneva: WHO Press.

Comments

0 comment